The September 14, 1970 extraction of CCN

Recon Team Moccasin

by Robert Morris

Foreword

When I learned that Richard Bittle, my crew chief aboard UH-1H

67-17261 in 1971, had started the "A101avn.org" website, I thought

that it would be great if I could contribute something worth posting.†† I began to go over some events in my mind,

trying to select a wartime experience that Ric's audience would be interested

in.† I thought that the story of what

happened to me during my first CCN flight would be a good one, a tale punctuated

with the humor that often accompanies even the most hazardous situations.† While developing the information, I came to

realize that the story of that day's mission was a much larger and more serious

one than what I had been contemplating, yet one that deserved to be told.† So I was surprised when I began discussing

the larger project with my fellow aviators and found that few of them

remembered the event at all.† One might

think that a mission resulting in the death of a soldier and the loss of an

aircraft would be easily recalled by everyone, but that was not the case.† This fact brought me back to the reality of

the risks normally involved in those missions, which were such that, at the

time, this particular case seemed to be merely routine.† With the passage of time and the luxury of

hindsight, what once seemed routine is now recognized as something

extraordinary.

I was fortunate to be able to contact enough of the

participants that many pieces of the puzzle can be put into place.† By its nature it must always remain

incomplete, and even our small cast of characters will not agree on all the

details, but that is not so important, for it does not affect the basic thrust

of the story.† My intent was to

illustrate the common bravery that was displayed on so many similar missions by

CCN recon team members and flight crews alike, the characteristic which forged

the special bonds of brotherhood that hold us together even now.† It is not a story of "heroes", but

one about regular soldiers who took their chances and did what needed to be

done to complete the mission and to save the lives of as many of their comrades

as possible.

I arrived in Vietnam on

or about July 20, 1970, and after requesting assignment to the 101st

Airborne Division as my first choice, I spent a week at SERTS (Screaming Eagle Replacement

Training School) at Camp Evans and eventually joined the Comancheros of Company

A, 101st Aviation Battalion about August 1.† For the first couple of weeks, the Company

Commander, Major Schneider, decided that he needed sandbags filled more than he

needed his newest peter pilot to get stick time, so I joined the mixed crew of

Warrant Officers and Enlisted Men on sandbag duty, helping to prepare for the

onset of the monsoon season.† A couple

of weeks passed before I got to do any real flying, and then only on routine

missions that allowed me to learn our Area of Operations and get some

experience in how combat aviation operations were conducted.† This included learning how to interact as

part of a four man crew, get all the radio traffic straightened out in my head,

avoid the path of friendly artillery fire, work with the people we supported on

the ground, plan the safest approach into a tight landing zone, and learn all

the other things necessary to conduct a successful helicopter operation.† I thought I had done pretty well in flight

school, but I realized that I had to go to the next step, which was to learn

how things were really done in a combat zone.†

It was this need for seasoning that was the basis for the Company policy

that New Guys didn't get assigned to fly CCN missions until they had mastered

the basics of in-country flight operations.

During the time that I

was learning the fundamentals, I heard other pilots in the O-club talking about

their CCN experiences, and I learned to treat the topic with some

reverence.† I knew that there had been

A/101 people lost on some of these missions, even in the brief period since I

had arrived in Nam.† I couldn't quite

imagine what the operations were like, but it became very clear to me that I'd

better have myself together when my time came to fly a CCN mission.†

I learned that CCN stood

for Command and Control North, which was a Studies and Observation Group (SOG)

operation.† Missions were usually

launched from the CCN compounds in Quang Tri, Phu Bai, and the Marble Mountain

facility in Danang.† An operation might

consist of the insertion of a recon team of about six men, maybe half of them

Americans and the other half from Southeast Asian ethnic tribes recruited by

SOG.† The key team members were the One-zero

(team leader), the One-one (assistant team leader), and the One-two (radio

operator).† The team would be flown to

the area of interest, often across the border into Laos, to be inserted into

pre-selected landing zones (LZs).† The

on-site operations would be run by a USAF Forward Air Controller (FAC

"Covey") in a spotter plane such as an O-2 or OV-10 fixed-wing

aircraft equipped with marking rockets.†

He would usually be accompanied by a CCN rider who assisted with

coordinating the ground operations. †The

UH-1H aircraft (sometimes called "Gnats") carrying the team would be

escorted by AH-1G Cobra gunships ("Dragonflies") which would

"prep" the landing zones and counter any enemy ground fire that might

be encountered.† On a few missions,

there was additional fire support provided by A-1E close-support

propeller-driven aircraft ("Spads"), and Covey had the ability to

call in additional airpower if necessary.†

Following a successful insertion, the recon team would pursue their

planned objective for a period of perhaps several days, after which another

flight would be dispatched to extract them and return them to their base.† If a recon team was discovered by the enemy,

they would make every possible attempt to escape and evade.† If they were not successful in these

efforts, the One-zero would call for an emergency helicopter extraction as a

last resort.† This was known as

declaring a "prairie fire".

On September 13, 1970,

Recon Team (RT) Moccasin was assigned the mission to insert into a location in

Laos, west of the A Shau Valley, in order to observe a particular river

junction and the NVA traffic crossing there.†

The position was on the side of a steep hill, on the northwest side of

the confluence of the rivers.† The

mission called for more than the usual amount of equipment, including starlight

scopes, a transponder, and gear for secure radio communications.† In addition, because the team would need to

maintain a static position while carrying out their observations, the One-zero,

SFC Pierce Durham, decided that he wanted to bring along plenty of

firepower.† Due to the heavy load of

equipment, he asked for volunteers to augment his team, which included George

Hewitt and a Vietnamese interpreter.† A

black soldier named Martin came forward, and Durham told him that he needed

someone to carry an M60 machine gun and ammunition:† Martin agreed to do the job.†

(When the others heard about Martin's responsibilities, they reminded

him of something they had told him previously that had made him uneasy:† that on some missions the NVA had used dogs

to hunt them down.† They joked with him

that the M60 could take care of any dog that the NVA might send after

him.)† The addition of a few indigenous

troops resulted in a reinforced team of about seven men.

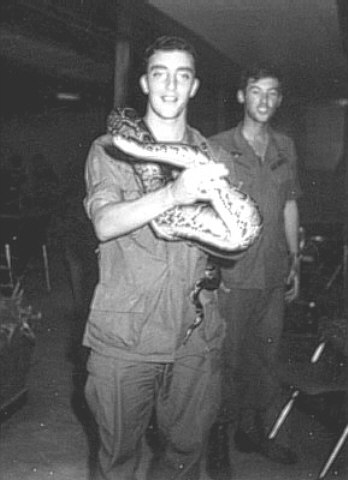

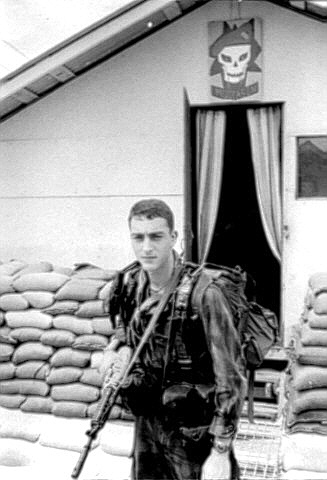

Photo on Left: With recon team names of Anaconda, Asp and Moccasin, it's no wonder that CCN harbored a boa constrictor. Friday afternoon feedings with live prey generally entertained a large audience. Photo on Right: George Hewitt dressed in his 1970 business suit. Note that the sign above the door indicates that the building belongs to RT Moccasin.

Photographs

are the property of George Hewitt and are used by permission

An aviation unit equipped

with cargo helicopters was approached with the request to transport the team to

the selected LZ.† Their response

indicated that the high elevation of the proposed LZ would result in lift

problems for their helicopters, and so the mission was declined.† An alternate plan was developed with lift

support to be provided by the smaller UH-1H utility helicopters of the Army's

101st Airborne Division.††

The insertion was performed in the afternoon of September 13.† After receiving the team's okay, the flight

departed the area.† From the LZ, the

team had to walk several kilometers to reach their intended observation

point.† SFC Durham proceeded to

establish an overnight position, directing that claymore mines be set up around

the perimeter to discourage any uninvited visitors.† During the night, the team listened to the sounds of generators

operating to the west, and passed the information back for use in planning

airstrikes.† On the morning of the 14th,

while observing the river junction, the team saw NVA soldiers heading in their

direction and realized that they had been spotted.† Due to the characteristics of the terrain, they knew that the

likelihood of evasion was remote.† The

NVA would set up on the hill above them, it would be too dangerous to move down

to the river, and trying to parallel the hillside with the enemy holding the

high ground wasn't a good option either, especially due to the lack of heavy

foliage cover.† The decision was made to

call for an evacuation by helicopter.

I remember well that

September 14, 1970 was the first time that I participated in a CCN extraction

from Laos.† I flew in the right seat as

copilot, with Jim Wallace, Comanchero 24, as the Aircraft Commander (AC) in the

left seat.† Our aircraft would be last

in the flight of four Comanchero UH-1H "slicks", going along as a

chase ship since the team could be pulled out by the first two birds.† I thought that this would provide me with a

good introduction to extraction operations, since we weren't necessarily going

to do anything other than orbit on standby, in the perfect position to

observe.† I sat back and paid careful

attention, for although I was young and foolish, I had developed a strong

interest in personal survival.

Things seemed to be going

along pretty well as we flew across the border and continued a few clicks

(kilometers) into Laos.† After

establishing radio contact and the team's position had been marked by Covey,

the lead ship established an approach path from the east to pick up the first

part of the team, while the accompanying Cobras hosed down the area, which had

become hot with enemy ground fire.† The

lead crew, flying aircraft 741, was made up of Frank Tigano as AC, Mike Victory

as copilot, J.J. Makool as crewchief, and Rick Campbell as doorgunner.† The LZ had a steep slope downward right to

left, surrounded by trees and only large enough to accommodate one ship at a

time.† Due to the conditions, Tigano

couldn't get low enough to make a touchdown and had to come to a high hover

while the ladder was lowered down on the right side of the aircraft to the

team.† While the pax (passengers) were

hooking up to the ladder, he experienced a combination of factors that was not

unusual for CCN extractions:† hot day,

high altitude, out-of-ground-effect hovering in an exposed position while

taking enemy ground fire!† While the

loading process was going on in the lead ship, Byron Edgington, commanding

chalk 2 (the second ship) in the flight, was forced to break off his final

approach and make a small orbit to the left in order to give Tigano the time to

complete his extraction.† Byron's crew

that day included Tom Nietsche as copilot and Gil Alvarado as crewchief.

The recon team members

realized that the enemy had moved troops up to the top of the hill and that

ground fire was now coming in heavily from that direction.† Durham had the indigenous soldiers climb the

lead ship's ladder first.† The first man

had hooked his STABO rig near the top of the ladder and two more were climbing

it while it was being steadied by George Hewitt.† Makool and Campbell, in the back of the ship, were feeding

information to help Tigano keep it properly positioned, while trying to assist

the team members and provide suppressive fire.†

As the fourth passenger hooked onto the ladder, Tigano experienced a

loss of pedal control, and the crew attempted to signal the last man to get

off.† Campbell's M60 machine gun jammed

at about this time, and so he reached for his M16 rifle.† Hewitt observed an explosion in the trees

just above the helicopter that he thought was caused by a B40/Rocket Propelled

Grenage type ordnance.† There were a

couple of loud bangs, and Victory felt a concussion that seemed as if someone

had hit the bottom of his seat with a baseball bat.† Within seconds the aircraft began to shudder, and both Makool and

Campbell knew that they were going down, even as Tigano shouted a warning.† Durham rolled himself down the hill when he

realized that the ship was crashing in.†

As it descended, the aircraft made a 180-degree turn to the right before

coming down slightly uphill from the team members' location, the rotor blades

coming apart as they smashed into the hillside.† Due to the uneven terrain, the ship proceeded to roll a couple of

turns down the slope, where it seemed to pause with its right side in the

dirt.† Makool immediately took the

opportunity to jump from the skyward side, only to have the ship make another

half roll and pin him across the thighs with its landing skid as its progress

was finally halted by a small tree that became lodged under the left side.† The top man on the ladder, whose rig had

been secured to it, was pinned under and crushed by the airframe.† Nothing could be done except to provide him

with a morphine injection to ease the pain of his mortal injuries.† The second man on the ladder was thrown

free, but was pinned down by his rucksack and uniform when the aircraft rolled

onto one arm.† The other team members

were thrown clear.† George Hewitt was

tossed down the hill, and when he opened his eyes he saw that the tailboom of

the aircraft was missing its tail rotor.†

Campbell, who had lost his M16 while the ship was tumbling down the

hill, jumped to the ground from the back of the ship, landing on Martin's back.† Martin handed his M60 off to the unarmed

Campbell, told him that he was going to free Makool from under the skid, and

proceeded to lift the skid enough to release the pressure from the crewchief's

legs.† Another team member grabbed

Makool by the wrists and pulled him free.†

Campbell attempted to put out some covering fire with the M60, but

discovered that it was out of ammunition, and so he tossed it away, his head

still spinning from the effects of the crash.†

Martin had moved to the soldier who was pinned by the arm.† He used a large knife to cut away the

indig's gear and dug under his arm in order to release him, but the trapped

soldier began to panic and severely lacerated his arm as he yanked it free:† he was afraid that his rescuer had intended

to free him by cutting it off!

In the front of the

aircraft, the pilots also had their hands full.† They were still in their seats in what was left of the

cockpit.† Mike Victory's front

windscreen was broken and he could see muzzle flashes up in the tree line.† When he tried to crawl out the window, the

cord connected to his flight helmet jerked him back.† When he removed the helmet, he fell out through the window

opening and tumbled several feet to the ground.† When he stood up, he saw someone shooting at him, so he pulled

out his pistol and returned fire, at which his opponent withdrew.† He then encountered Martin trying to free

the team member from under the skid, saw Campbell and asked him about the rest

of the crew.† Rick replied that Tigano

hadn't come out of the ship yet.†

Victory went back around to the uphill side of the fuselage, where enemy

fire was still coming in from the tree line above.† He climbed back inside the†

cargo area and saw that Tigano was stuck in the left seat, pinned

against the ground and the cyclic stick.†

He released the back of the pilot's seat, pulled him out, and noticed

that his face was covered with blood.†

There was a strong odor of fuel as the ruptured cells spilled their

contents down the hillside.† In a dazed

state, Tigano began to look around for the crashed aircraft's KY-28 secure

radio and logbook.† Victory yelled to

him to get out, that there was another aircraft hovering in above them, then

crawled out and encountered Martin again, who was working with the crushed team

member.† Martin told Victory that

nothing more could be done, and to get on the approaching helicopter.† Meantime, Tigano was finally able to clear

his head and realized what was happening, dropped what he had been doing, and

with a rush of adrenaline he climbed out of the smashed aircraft and ran past

Victory on his way to the second ship's ladder.

Byron Edgington had

started his left turn prior to Tigano's ship going down, and by the time he had

completed his circle, he saw the lead helicopter lying on its side, with people

scurrying out of it like bees from a hive.†

He continued his approach in to a high hover and directed the gunner to

lower the ladder down on the right side of the aircraft.† Following standard procedure, the downed air

crew was evacuated first, to be followed by the team members, whose training

would make them much better able to survive in case anyone had to be left on

the ground.† Faces began to appear as

men climbed the ladder and boarded.†

Makool and Tigano were able to get inside, and possibly Campbell as

well.† Mike Victory got to the ladder

just as Tigano finished climbing into the cargo hold.† He tried to climb the ladder, but he was still wearing his heavy

armored chest protector ("chicken plate"), and also was reluctant to

climb any higher while the gunner was firing an M60 right above him.† So he sat down on a rung of the ladder and

held on for the ride while Edgington tried to coax his bird out of the LZ

holding 50 pounds of torque and trying to keep the engine RPM from bleeding

down to the warning-horn level.† He was

able to get out without doing any damage to Victory, who had a close visit with

some tree branches on the way out.† As

they were departing, Mike saw muzzle flashes that seemed to be coming from all

around, and he replied by firing back at them with his revolver.† When he ran out of bullets, he threw the

empty pistol at the muzzle flashes and then concentrated on hanging on to the

ladder, as he had no equipment to clip on with.† Edgington's gunner exchanged waves with Victory, who had a lot of

Tigano's blood on him, as well as some of his own.† Edgington increased his airspeed and began climbing to altitude

to make his way back across the A Shau to a firebase where he could get Victory

back inside the ship.† As he climbed,

the wind produced by the forward airspeed combined with the sharp drop in

temperature, making Victory feel very cold.†

His shivers also had a psychological component:† as the airspeed increased, Victory noticed

that he and the ladder were being blown back, closer to the path of the

menacing tail rotor.

Dave Trujillo was flying

in chalk 3 and also witnessed the lead aircraft go down with troops on the

ladder.† They made their approach with

their 60s firing, and Dave saw the fuel flowing down the hill as he got closer,

and was amazed that the wreck wasn't on fire.†

His ship was able to extract the first part of the recon team, leaving

the remaining three or four men for the last ship.

My relaxed ride in the

trail ship had all of a sudden turned into a serious situation.† During the course of the evacuation, Covey

had called in additional gun support, eventually expending eight Cobra loads of

ordnance.† But we were the only remaining

lift ship, there would be nobody standing by to pick us up if we went down.† Jim Wallace began our approach, instructing

me to lightly get on the controls with him, ready to take over in case anything

should happen to him.† We came to a high

hover, let down our ladder, and the remaining men quickly started getting on

while our gunners were blasting the surrounding area with their M60s to keep

the enemy on the defensive.† In the rush

to clear the area, the pax hooked on the ladder and didn't take the time to

climb aboard.† This would have been fine

except for the fact that we had most of the US troops, who outweighed the

indigs, and everybody was on the ladder on the right side of the ship.† It was beginning to look like a replay of

Tigano's initial predicament.† I could

feel that Jim had the cyclic stick all the way to the left, bouncing off the

stop, when our gunner was calling for us to bring the ship left and not let it

drift into the trees on the right side.†

Jim made a split-second decision and immediately pulled all the torque

he could to raise us up above the trees before we drifted into them.† He got us clear of the trees, but the ship

didn't fly well, being so far out of lateral center of gravity (CG)

limits.† We eventually made a slow right

turn and got headed back in a generally easterly direction.† Jim knew that he was going to have a hell of

a time trying to get our pax back on the ground without injury, and without

bringing an out of control chopper down on top of them.† His next move was purely logical, though

somewhat injurious to my pride:† he

ordered the crew to pull the release handles on the back of my armored seat and

drag me out of my chair, and he told me to go over and sit on the left side of

the cargo area.† So there I was on my

first CCN extraction, fulfilling the lowly, yet important role of a

counterweight.† It occurred to me that

only a few weeks before I had been filling sandbags, and here I was being used as a sandbag!

While we were working

through our tribulations, chalks 2 and 3 were able to get back across the A

Shau Valley to a friendly base where they succeeded in getting all their pax

inside.† To those who saw him, Mike

Victory appeared to be nearly frozen from his ride.† With his energy expended, he was too tired to stand up and

untangle his legs from the ladder.† An

American Lieutenant came over and pulled him out from under the aircraft so it

could land.† The Lieutenant surmised

that Victory had been the pilot of a downed ship, and without knowing the

particulars, said that he had a recon team that could go out and secure his

aircraft!† Victory thought to himself

that this Lieutenant didn't want to go anywhere near where he had come from.

Back in the trail ship,

Jim Wallace had decided there was no way that he was going to try to put down

at a small firebase, so we carried our pax all the way back to Firebase

Birmingham.† The team members hanging

below us were still in communication with the Covey plane, and they heard that

one of the options being considered was to put them down in the Perfume River

adjacent to the firebase.† This idea was

rejected, and Wallace decided to put them down at the Birmingham strip, where

he could flare the ship in so as to unburden the weight of our ladder

passengers and correct our unbalanced condition before trying to come to a

hover.† He set up his approach down the

strip, slowing the unstable ship as much as he dared before setting down.† Pierce Durham decided that he didn't want to

be dragged down the length of the strip, so he purposely dropped off the ladder

when he was still two or three feet off the ground.† This had the effect of partially alleviating the unbalanced

condition, and reduced the amount of dragging that the other ladder passengers

had to endure before finally coming to a halt.†

We landed and shut down the aircraft, exhausted and dripping with sweat.

†I think somebody apologized to the pax

for dragging them, but they didn't seem to be much bothered.† Like us, they were happy to have survived,

and nothing else really mattered at the time.†

The picture was taken looking back towards the coast, and clearly shows the Birmingham strip alongside the "highway" and the river. On the left of the strip is the POL point that we so often refueled at after long missions to the west.†† The photograph property of Steve Nirk, and used by permission.

Except for those who were wounded, nobody really remembers very much about the

rest of the day.† At the hospital, Frank

Tigano discovered that shrapnel had pierced his upper lip, sliced his two front

teeth in half, and exited out his lower lip.†

The indig with the lacerated arm had his wound treated and bandaged up.† Some others had small pieces of shrapnel

removed that they felt were insignificant.

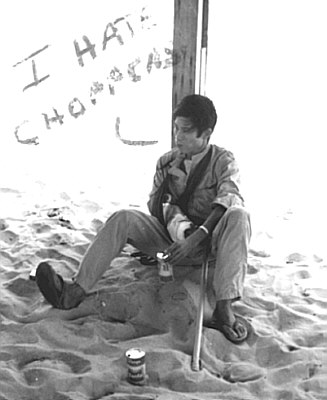

A day at the beach didn't seem to do much good for the indig who had been cut free by Martin. As noted, he may have been thinking, "I hate choppers". Note the heavily bandaged arm.

Photograph

is the property of George Hewitt and is used by permission

Back at the CCN

debriefing, Pierce Durham discussed what had happened to the lost soldier.† He was aware that there had been some suspicion

that the doomed indig was actually an enemy infiltrator.† Durham was now convinced of it:† when he had checked the perimeter on the

night of the 13th, he found that the indig had placed his claymore mines facing

in, instead of out towards the enemy.†

Durham hadn't wanted to pursue the matter until returning from the

field, but fate had taken the situation out of his hands.

The CCN team members were

kept at Phu Bai briefly and then were brought down to the Marble Mountain base

where a Lieutenant Colonel gave the teams a lecture about the rate that

equipment was being left behind on their missions.† A display had been set up to demonstrate how many items had been

abandoned in the previous months.† This

frosted Durham and the others, who were much more concerned about lost men than

anything that money could buy.† As an

E-7, SFC Durham was the senior One-zero, most of the others being E-5s or

E-6s.† When Durham got up and walked out

of the meeting, it didn't take long for the others to follow.† His expression of displeasure earned him an

invitation to pack his bags, so Durham headed back down to the base at Nha

Trang, where he finished out the remainder of his tour as an instructor in

recon techniques.

People started calling

J.J. Makool "Crash", which replaced the previous nickname of

"On-fire-Makool" that he had earned two months earlier when half his

mustache was burned off in another CCN incident.† This time the nickname stuck.

Rick Campbell hadn't told

his folks about the close call, but when he returned home from his tour of duty

three weeks after the incident, his mother showed him the only article about

the war that she had saved from the Detroit newspaper.† He couldn't believe what he read:† it said something like "Army Chopper

Strays Over Laos Border, Shot Down 9/14/70".

Mike Victory remembers

meeting Martin again several months later at the Marble Mountain compound, and

Frank Tigano also recalls seeing him at Phu Bai.† His current status is unknown, but if he is still living he should

know that there is at least one crewchief that would like to buy him a drink.

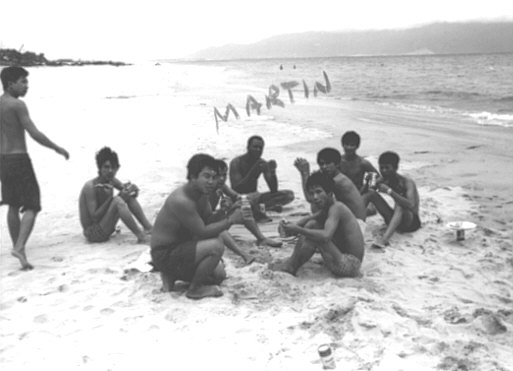

Martin and the "little people" enjoying their day at the beach.

Photograph

is the property of George Hewitt and is used by permission

Acknowledgments

Input from the following participants was crucial to detailing

the mission:† Gil Alvarado, Rick

Campbell, Pierce Durham, Byron Edgington, George Hewitt, J.J. Makool, Tom

Nietsche, Frank Tigano, Dave Trujillo, Mike Victory, and Jim Wallace.

Copyright „ Robert E. Morris,

2001.† All rights reserved

© This Story and pictures are under copyright to there authors/owners and may not be copied or used in any matter without the permission of Author. All Rights Reserved.